This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Organisational change – On leadership… (5 of 5)

09 June 2022

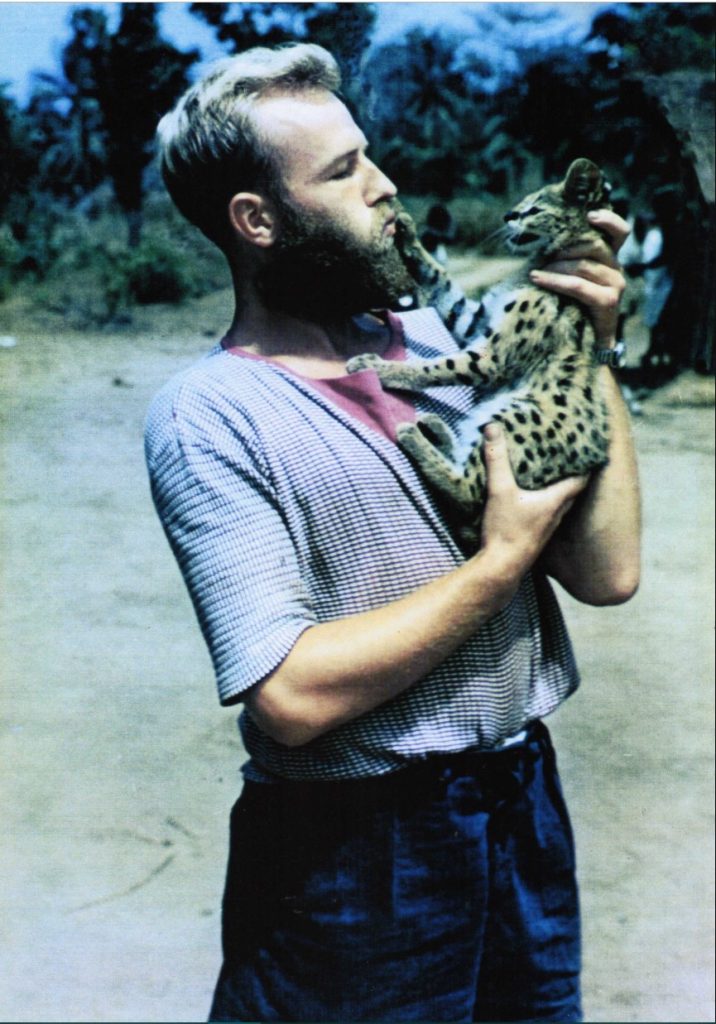

My father with a serval cub while leading a map-making expedition in Africa

Part five of a series of thought pieces by Ben Story, COO of SDCL

“There is nothing more difficult, more doubtful of success or more dangerous than to initiate a new order of things. For the reformer has enemies in all those who profit by the old order, and only lukewarm defenders in all those who would profit by the new order.”

As Niccolo Machiavelli wrote in The Prince in the 16th Century, seeking change is fraught with risk. Nonetheless, some people cannot resist: they are naturally drawn to opportunities and dismayed by mediocrity. If you are such a person, you are an outlier. You could be a change leader who finds joy in driving core momentum.(1)

Thirty years ago, senior executives were called managers; now they are called leaders. There is a reason for this: management suggests the optimisation of a fixed set of parameters; whereas, leadership conveys a sense of opportunity and change. All organisations need good managers and, despite the evolution in language, day-to-day management of the status quo dominates many established organisations. If they want to embed a continuous strategic change capability, organisations also need to cultivate good change leaders.

Firstly, recognise that change requires people who are unorthodox, non-conformist and creative. This does not mean that such people do not want to belong to an organisation; it does not mean that they are not team players. It means that organisations need to be truly diverse and inclusive. Here, the concept of psychological safety is very important. Professor Amy Edmondson defines psychological safety as “a shared belief held by members of a team that the team is safe for interpersonal risk taking”. Google’s research on team effectiveness revealed that “Of the five key dynamics of effective teams that the researchers identified, psychological safety was by far the most important”.(2)

Secondly, empower change leaders by providing them with clear mandates, constant reassurance and deserved recognition. Organisations need to look at how they measure and reward performance, which is generally based on management metrics, rather than leadership outcomes. When I studied Japanese history and society at university a particular saying stuck in my mind, “The nail that sticks out gets hammered down”. I have subsequently discovered many similar cultural phenomena all around the world, such as Tall Poppy Syndrome.(3)

Thirdly, build a broad coalition for change. Leading change can be lonely and painful, and it is easy to feel shunned, isolated and foolish. There is no need to take solace in the Hero’s Journey: there will be numerous people throughout the organisation who are desperate for change. Successful change leaders, like Lord Horatio Nelson, an outlier who transformed naval warfare in a series of remarkable victories, go to exceptional lengths to cultivate strong supporting teams.(4)

Fourthly, pick your battles. Big change can start small. Create a portfolio of change projects, including some which can be run in parallel and some “easy wins” that can demonstrate success and build confidence. It is important to seize liminal moments, where there is a window of opportunity, but also to value temporisation, where there are multiple viable options. And be kind and generous to those affected.

Indeed, at any point in time, all organisations have a limit to how much change they can undertake (or a “change quota”).(5) A useful tool for selecting where to focus draws upon Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs(6): prioritise where an organisation should truly pioneer to generate a distinct competitive advantage; target where an organisation should lead to maintain overall competitiveness; and identify where an organisation should follow best practice to sustain overall competitiveness. If the change needed to be competitive is greater than the change quota, an organisation is probably too complex.

Fifthly, make change a campaign. Make change meaningful by communicating comprehensively, consistently and continuously using multiple formats, on multiple channels, cross-referencing practical outcomes. As my boss at Morgan Stanley used to tell me, “Being right is just a good starting point.” People will not support change unless they progress from awareness to understanding to feeling. Organisational change is socially transmitted so emotions are more important than logic.

Finally, be resolute! Change is hard. Expect lots of failures and disappointments. Moreover, expect latency – change projects need to accumulate and consolidate before organisational change reaches the “escape velocity” needed for core momentum. I have always liked Samuel Beckett’s maxim, “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

Good luck! I would be thrilled if these pieces have provided some useful insights on organisational change and I hope that you find joy as a change leader. I certainly intend to.

(1) In my earlier piece “On change…” I defined “core momentum” as a continuous strategic change capability which ensures that an organisation is constantly exploring, learning and growing.

(2) See re:Work Tool: Foster psychological safety from Google.

(3) See Tall poppy syndrome on Wikipedia.

(4) See The Pursuit of Victory: The Life and Achievement of Horatio Nelson by Roger Knight.

(5) “Most Advanced. Yet Acceptable” (or “MAYA”) is a concept that recognises the idea of a change quota. MAYA was promoted by the industrial designer, Raymond Loewy, to give users the most advanced design, but not more advanced than what they were able to accept and embrace.

(6) See Maslow’s hierarchy of needs on Wikipedia.